The heat below is shifting the ground beneath Chicago

Beneath the city of Chicago’s high-rise Art Deco towers, its multilevel streets and its busy subway and rail lines, the ground is sinking, and not just for the reasons you might expect. Since the mid-20th century, the city’s surface and the land between it and the rock have warmed an average of 5.6 degrees Fahrenheit, according to a new study from Northwestern University.

All that heat, which comes mostly from basements and other underground structures, has caused layers of sand, clay and rock to shrink or swell by several millimeters under some buildings over the decades, which can worsen cracks and faults in walls and foundations. enough for.

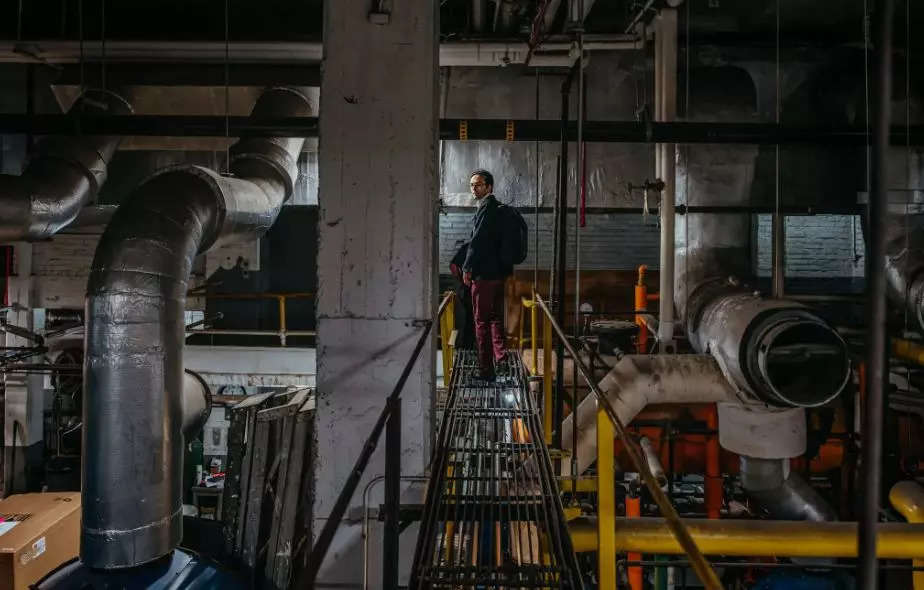

All around you, you have sources of heat,” said study author Alessandro F. said Rota Loria, who was walking with a backpack through Millennium Station, a commuter rail terminal beneath the city’s Loop district. “These are things that people don’t see, so it’s as if they don’t exist.” It’s not just Chicago. In large cities around the world, surface mercury is rising as humans burn fossil fuels.

But heat is also seeping out of basements, parking garages, train tunnels, pipes, sewers and electrical wires and into the surrounding Earth, a phenomenon scientists have dubbed “underground climate change.”

Metro tunnels are heating up due to rising underground temperatures, which can lead to extremely hot tracks and steam-shower conditions for commuters. And, over time, they cause small changes in the ground beneath buildings, which can create structural stresses, the effects of which are not noticeable until suddenly.

The heat below is shifting the ground beneath Chicago

Asal said, “Today, you are not seeing that problem.” Biedarmaghz is a Senior Lecturer in Geotechnical Engineering at the University of New South Wales in Australia. “But in the next 100 years, there is a problem.

And if we sit for another 100 years and wait another 100 years to solve it, it’s going to be a big problem.” Biedermaghz has studied underground heat in London, but was not involved in the research in Chicago.

In Chicago, Rotta Loria, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern, has installed more than 150 temperature sensors above and below the loop’s surface to assess climate change underground.

They combined three years’ worth of readings from these sensors with a detailed computer model of the district’s basements, tunnels and other structures to work out how the ground has warmed at various depths between 1951 and now, and 2051 from now.

How hot will it be? Near some of the sources of heat they found, the ground beneath Chicagoans’ feet has warmed up to 27 degrees Fahrenheit over the past seven decades. This has caused soil layers under some buildings to expand or shrink by up to half an inch.

They found that warming and land deformation are occurring more slowly now than in the 20th century, as the Earth is closer to Earth-like. As warm as the cellars and tunnels buried within it. At worst, those structures will stay warm instead of dissipating heat into the ground around them. Rota Loria’s findings were published Tuesday in the Journal of Communications Engineering.

This, he said, would be the most effective way to address the problem for building owners and tunnel operators. The insulation has to be improved so that less heat leaks into the earth. They could also add heat to the work.

Rota Loria is chief technology officer at Enerdrepp, a startup in Switzerland that makes panels that absorb ambient heat in tunnels and parking garages and use it to run electric heat pumps, cutting down on utility bills. The company has installed 200 of its panels in a supermarket parking garage near Lausanne as a pilot project.

Rota Loria intentionally did not include one factor in his estimate of underground warming in Chicago: climate change at the city’s surface.

Warm weather heats the upper layers of the soil. But Rota Loria’s calculations assume that air temperatures in Chicago will remain at their average recent levels until 2051 – that is, their estimates do not include climate scientists’ projections for future global warming.

Nor do they account for the fact that, as we continue to warm the planet, larger buildings will likely use more air conditioning and pump even more waste heat into the ground. The reason for these omissions, Rota Loria said, is that he is trying to find a conservative lower bound on underground warming, not a worst-case scenario.

“It already shows there is a problem,” he said. The office of Chicago’s mayor, Brandon Johnson, did not respond to requests for comment. On a recent morning, Rotta Loria, a Northwestern doctoral candidate in civil engineering, and Anjali Thota, took a reporter and a photographer on a tour of its network of temperature sensors, which detect a kind of invisible city beneath the city.

Rotta Loria said the Chicago Transit Authority did not allow him to install sensors in subway stations because of concerns. That people would mistake him for a bomb detonator. But he and his team have managed to place sensors in many other known and lesser-known places: on commuter rail platforms and at service entrances behind tall buildings, in lush Millennium Park and under Walker Drive, on cavernous concrete pavements.

The lair that has been made famous is the car chase in the movies “The Blues Brothers” and “The Dark Knight.” The sensors themselves are unknown: a white plastic box with a button and two indicator lights.

Each Rotta Loria costs $55. The temperature information they collect – a reading every minute or every 10 minutes, depending on location – is downloaded to a phone via Bluetooth, which means Rota Loria and his students need to periodically update their data.

To get about 20,000 records would have to meet them in person. Overall per day. Many sensors have been swiped or disappeared over the years, leaving 100 in service. The heat below is shifting the ground beneath Chicago in 2023.

In the Millennium Garage, an underground parking complex, one of them is zip-tied to a pipe behind a column. “That’s it, huh?” said Admir Sefo, an executive at the garage, looking at the widget. “And no one found them?” “It is difficult for us to even find them,” said Thota. He has saved their locations on Google Maps, but underground, there is often no cell reception, forcing him to look around.

Source link | Texas

Be First to Comment